- Home

- Nora Roberts

Nora Roberts's Circle Trilogy Page 3

Nora Roberts's Circle Trilogy Read online

Page 3

“He is vampyre. He must teach you, and he must fight beside you. There can be no victory without him.”

Such size, he thought. Buildings of silver and stone taller than any cathedral. “Will the war be in this place, in this New York?”

“You will be told where, you will be told how. And you will know. Now you must go, take what you need. Go to your family and give them their shields. You must leave them quickly, and go to the Dance of the Gods. You will need your skill, and my power, to pass through. Find your brother, Hoyt. It is time for the gathering.”

He woke by the fire, the blanket wrapped around him. But he saw it hadn’t been a dream. Not with the blood drying on the palm of his hand, and the silver crosses lying across his lap.

It was not yet dawn, but he packed books and potions, oatcakes and honey. And the precious crosses. He saddled his horse, and then, as a precaution, cast another protective circle around his cottage.

He would come back, he promised himself. He would find his brother, and this time, he would save him. Whatever it took.

As the sun cast its first light, he began the long ride to An Clar, and his family home.

Chapter 2

He traveled north on roads gone to mud from the storm. The horrors and the wonders of the night played through his mind as he hunched over his horse, favoring his aching ribs.

He swore, should he live long enough, he would practice healing magic more often, and with more attention.

He passed fields where men worked and cattle grazed in the soft morning sunlight. And lakes that picked up their blue from the late summer sky. He wound through forests where the waterfalls thundered and the shadows and mosses were the realm of the faerie folk.

He was known here, and caps were lifted when Hoyt the Sorcerer passed by. But he didn’t stop to take hospitality in one of the cabins or cottages. Nor did he seek comfort in one of the great houses, or in the conversations of monks in their abbeys or round towers.

In this journey he was alone, and above battles and orders from gods, he would seek his family first. He would offer them all he could before he left them to do what he’d been charged to do.

As the miles passed, he struggled to straighten on his horse whenever he came to villages or outposts. His dignity cost him considerable discomfort until he was forced to take his ease by the side of a river where the water gurgled over rock.

Once, he thought, he had enjoyed this ride from his cottage to his family home, through the fields and the hills, or along the sea. In solitude, or in the company of his brother, he had ridden these same roads and paths, felt this same sun on his face. Had stopped to eat and rest his horse at this very same spot.

But now the sun seared his eyes, and the smell of the earth and grass couldn’t reach his deadened senses.

Fever sweat slicked his skin, and the angles of his face were keener as he bore down against the unrelenting pain.

Though he had no appetite, he ate part of one of the oatcakes along with more of the medicine he’d packed. Despite the brew and the rest, his ribs continued to ache like a rotted tooth.

Just what good would he be in battle? he wondered. If he had to lift his sword now to save his life he would die with his hands empty.

Vampyre, he thought. The word fit. It was erotic, exotic, and somehow horrible. When he had both time and energy, he would write down more of what he knew. Though he was far from convinced he was about to save this world or any other from some demonic invasion, it was always best to gather knowledge.

He closed his eyes a moment, resting them against the headache that drummed behind them. A witch, he’d been told. He disliked dealing with witches. They were forever stirring odd bits of this and that in pots and rattling their charms.

Then a scholar. At least he might be useful.

Was the warrior Cian? That was his hope. Cian wielding sword and shield again, fighting alongside him. He could nearly believe he could fulfill the task he’d been given if his brother was with him.

The one with many shapes. Odd. A faerie perhaps, and the gods knew just how reliable such creatures were. And this was somehow to be the front line in the battle for worlds?

He studied the hand he’d bandaged that morning. “Better for all if it had been dreaming. I’m sick and tired is what I am, and no soldier at the best of it.”

Go back. The voice was a hissing whisper. Hoyt came to his feet, reaching for his dagger.

Nothing moved in the forest but the black wings of a raven that perched in shadows on a rock by the water.

Go back to your books and herbs, Hoyt the Sorcerer. Do you think you can defeat the Queen of the Demons? Go back, go back and live your pitiful life, and she will spare you. Go forward, and she will feast on your flesh and drink of your blood.

“Does she fear to tell me so herself then? And so she should, for I will hunt her through this life and the next if need be. I will avenge my brother. And in the battle to come, I will cut out her heart and burn it.”

You will die screaming, and she will make you her slave for eternity.

“It’s an annoyance you are.” Hoyt shifted his grip on the dagger. As the raven took wing he flipped it through the air. It missed, but the flash of fire he shot out with his free hand hit the mark. The raven shrieked, and what dropped to the ground was ashes.

In disgust Hoyt looked at the dagger. He’d been close, and would likely have done the job if he hadn’t been wounded. At least Cian had taught him that much.

But now he had to go fetch the bloody thing.

Before he did, he took a handful of salt from his saddlebags, poured it over the ashes of the harbinger. Then retrieving his dagger, he went to his horse and mounted with gritted teeth.

“Slave for all eternity,” he muttered. “We’ll see about that, won’t we?”

He rode on, hemmed in by green fields, the rise of hills chased by cloud shadows in light soft as down. Knowing a gallop would have his ribs shrieking, he kept the horse to a plod. He dozed, and he dreamed that he was back on the cliffs struggling with Cian. But this time it was he who tumbled off, spiraling down into the black to crash against the unforgiving rocks.

He woke with a start, and with the pain. Surely this much pain meant death.

His horse had stopped to crop at the grass by the side of the road. There a man in a peaked cap built a wall from a pile of steely gray rock. His beard was pointed, yellow as the gorse that rambled over the low hill, his wrists thick as tree limbs.

“Good day to you, sir, now that you’ve waked to it.” The man touched his cap in salute, then bent for another stone. “You’ve traveled far this day.”

“I have, yes.” Though he wasn’t entirely sure where he was. There was a fever working in him; he could feel the sticky heat of it. “I’m to An Clar, and the Mac Cionaoith land. What is this place?”

“It’s where you are,” the man said cheerfully. “You’ll not make your journey’s end by nightfall.”

“No.” Hoyt looked down the road that seemed to stretch to forever. “No, not by nightfall.”

“There’d be a cabin with a fire going beyond the field, but you’ve not time to bide here. Not when you’ve so far yet to go. And time shortens even as we speak. You’re weary,” the man said with some sympathy. “But you’ll be wearier yet before it’s done.”

“Who are you?”

“Just a signpost on your way. When you come to the second fork, go west. When you hear the river, follow it. There be a holy well near a rowan tree, Bridget’s Well, that some now call saint. There you’ll rest your aching bones for the night. Cast your circle there, Hoyt the Sorcerer, for they’ll come hunting. They only wait for the sun to die. You must be at the well, in your circle, before it does.”

“If they follow me, if they hunt me, I take them straight to my family.”

“They’re no strangers to yours. You bear Morrigan’s Cross. It’s that you’ll leave behind with your blood. That and your faith.” The man’s eyes were pale and gray, and f

or a moment, it seemed worlds lived in them. “If you fail, more than your blood is lost by Samhain. Go now. The sun’s in the west already.”

What choice did he have? It all seemed a dream now, boiling in his fever. His brother’s death, then his destruction. The thing on the cliffs that called herself Lilith. Had he been visited by the goddess, or was he simply trapped in some dream?

Maybe he was dead already, and this was merely a journey to the afterlife.

But he took the west fork, and when he heard the river, turned his horse toward it. Chills shook him now, from the fever and the knowledge that the light was fading.

He fell from his horse more than dismounted, and leaned breathlessly against its neck. The wound on his hand broke open and stained the bandage red. In the west, the sun was a low ball of dying fire.

The holy well was a low square of stone guarded by the rowan tree. Others who’d come to worship or rest had tied tokens, ribbons and charms, to the branches. Hoyt tethered his horse, then knelt to take the small ladle and sip the cool water. He poured drops on the ground for the god, murmured his thanks. He laid a copper penny on the stone, smearing it with blood from his wound.

His legs felt more full of water than bone, but as twilight crept in, he forced himself to focus. And began to cast his circle.

It was simple magic, one of the first that comes. But his power came now in fitful spurts, and made the task a misery. His own sweat chilled his skin as he struggled with the words, with the thoughts and with the power that seemed a slippery eel wriggling in his hands.

He heard something stalking in the woods, moving in the deepest shadows. And those shadows thickened as the last rays of sunlight eked through the cover of trees.

They were coming for him, waiting for that last flicker to die and leave him in the dark. He would die here, alone, leave his family unprotected. And all for the whim of the gods.

“Be damned if I will.” He drew himself up. One chance more, he knew. One. And so he ripped the bandage from his hand, used his own blood to seal the circle.

“Within this ring the light remains. It burns through the night at my will. This magic is clean, and none but clean shall bide here. Fire kindle, fire rise, rise and burn with power bright.”

Flames shimmered in the center of his circle, weak, but there. As it rose, the sun died. And what had been in the shadows leaped out. It came as a wolf, black pelt and bloody eyes. When it flung itself into the air, Hoyt pulled his dagger. But the beast struck the force of the circle, and was repelled.

It howled, snapped, snarled. Its fangs gleamed white as it paced back and forth as if looking for a weakness in the shield.

Another joined it, skulking out of the trees, then another, another yet, until Hoyt counted six. They lunged together, fell back together. Paced together like soldiers.

Each time they charged, his horse screamed and reared. He stepped toward his mount, his eyes on the wolves as he laid his hands upon it. This at least, he could do. He soothed, lulling his faithful mare into a trance. Then he drew his sword, plunged it into the ground by the fire.

He took what food he had left, water from the well, mixed more herbs—though the gods knew his self-medicating was having no good effect. He lowered to the ground by the fire, sword on one side, dagger on the other and his staff across his legs.

He huddled in his cloak shivering, and after dousing an oatcake with honey, forced it down. The wolves sat on their haunches, threw back their heads, and as one, howled at the rising moon.

“Hungry, are you?” Hoyt muttered through chattering teeth. “There’s nothing here for you. Oh, what I wouldn’t give for a bed, some decent tea.” He sat, the fire dancing in his eyes until they began to close. As his chin drooped to his chest, he’d never felt so alone. Or so unsure of his path.

He thought it was Morrigan who came to him, for she was beautiful and her hair as bold as the fire. It fell straight as rain, its tips grazing her shoulders. She wore black, a strange garb, and immodest enough to leave her arms bare and allow the swell of her breasts to rise from the bodice. Around her neck she wore a pentagram with a moonstone in its center.

“This won’t do,” she said in a voice that was both foreign and impatient. Kneeling beside him, she laid her hand on his brow, her touch as cool and soothing as spring rain. She smelled of the forest, earthy and secret.

For one mad moment, he longed to simply lay his head upon her breast and sleep with that scent filling his senses.

“You’re burning up. Well, let’s see what you have here, and we’ll make do.”

She wavered in his vision a moment, then recrystallized. Her eyes were as green as the goddess’s, but her touch was human. “Who are you? How did you get within the circle?”

“Elderflower, yarrow. No cayenne? Well, I said we’d make do.”

He watched as she busied herself, as women would, dipping water from the well, heating it with his fire. “Wolves,” she murmured, shivered once. And in that shudder, he felt her fear. “Sometimes I dream of the black wolves, or ravens. Sometimes it’s the woman. She’s the worst. But this is the first time I’ve dreamed of you.” She paused, and looked at him for a long time with eyes of deep and secret green. “And still, I know your face.”

“This is my dream.”

She gave a short laugh, then sprinkled herbs in the heated water. “Have it your way. Let’s see if we can help you live through it.”

She passed her hand over the cup. “Power of healing, herbs and water, brewed this night by Hecate’s daughter. Cool his fever, ease his pain so that strength and sight remain. Stir magic in this simple tea. As I will, so mote it be.”

“Gods save me.” He managed to prop himself on an elbow. “You’re a witch.”

She smiled as she stepped to him with the cup. And sitting beside him, braced him with an arm around his back. “Of course. Aren’t you?”

“I’m not.” He had just enough energy for insult. “I’m a bloody sorcerer. Get that poison away from me. Even the smell is foul.”

“That may be, but it should cure what ails you.” She simply cradled his head on her shoulder. Even as he tried to push free, she was pinching his nose closed and pouring the brew down his throat. “Men are such babies when they’re sick. And look at your hand! Bloody and filthy. I’ve got something for that.”

“Get away from me,” he said weakly, though the smell of her, the feel of her was both seductive and comforting. “Let me die in peace.”

“You’re not going to die.” But she gave the wolves a wary glance. “How strong is your circle?”

“Strong enough.”

“Hope you’re right.”

Exhaustion—and the valerian she’d mixed in the tea—had his head drooping again. She shifted, so she could lay his head in her lap. And there she stroked his hair, kept her eyes on the fire. “You’re not alone anymore,” she said quietly. “And I guess, neither am I.”

“The sun…How long till dawn?”

“I wish I knew. You should sleep now.”

“Who are you?”

But if she answered, he didn’t hear.

She was gone when he woke, and so was the fever. Dawn was a misty shimmer letting thin beams eke through the summer leaves.

Of the wolves there was only one, and it lay gored and bloody outside the circle. Its throat had been ripped open, Hoyt saw, and its belly. Even as he gained his feet to step closer, the sun beamed white through those leaves, struck the carcass.

It erupted into flame that left nothing behind but a scatter of ashes on blackened earth.

“To hell with you, and all like you.”

Turning away, Hoyt busied himself, feeding his horse, brewing more tea. He was nearly done when he noticed his palm was healed. Only the faintest scar remained. He flexed his fingers, held his hand up to the light.

Curious, he lifted his tunic. Bruises still rained over his side, but they were fading. And when he tested, he found he could move without pain.

&n

bsp; If what had come to him in the night had been a vision rather than a product of a fever dream, he supposed he should be grateful.

Still, he’d never had a vision so vivid. Nor one who’d left so much of itself behind. He swore he could smell her still, and hear the flow and cadence of her voice.

She’d said she’d known his face. How strange that somewhere in the center of him, he felt he’d known hers.

He washed, and while his appetite had come back strong, he had to make do with berries and a heel of tough bread.

He closed the circle, salted the blackened earth outside it. Once he was in the saddle, he set off at a gallop.

With luck, he could be home by midday.

There were no signs, no harbingers, no beautiful witches on the rest of his journey. There were only the fields, rolling green, back to the shadow of mountains, and the secret depths of forest. He knew his way now, would have known it if a hundred years had passed. So he sent his mount on a leap over a low stone wall and raced across the last field toward home.

He could see the cook fire. He imagined his mother sitting in the parlor, tatting lace perhaps, or working on one of her tapestries. Waiting, hoping for news of her sons. He wished he brought her better.

His father might be with his man of business or out riding the land, and his married sisters in their own cottages, with young Nola in the stables playing with the pups from the new litter.

The house was tucked in the forest, because his grandmother—she who had passed power to him, and to a lesser extent, Cian—had wanted it so. It stood near a stream, a rise of stone with windows of real glass. And its gardens were his mother’s great pride.

Her roses bloomed riotously.

One of the servants hurried out to take his horse. Hoyt merely shook his head at the question in the man’s eyes. He walked to the door where the black banner of mourning still hung.

Inside, another servant was waiting to take his cloak. Here in the hall, his mother’s, and her mother’s tapestries hung, and one of his father’s wolfhounds raced to greet him.

A Little Magic

A Little Magic Vision in White

Vision in White True Betrayals

True Betrayals The Next Always

The Next Always A Man for Amanda

A Man for Amanda Born in Fire

Born in Fire Tribute

Tribute Night Moves

Night Moves Dance Upon the Air

Dance Upon the Air The Name of the Game

The Name of the Game Jewels of the Sun

Jewels of the Sun River's End

River's End Public Secrets

Public Secrets Homeport

Homeport Private Scandals

Private Scandals The Witness

The Witness Blithe Images

Blithe Images Hidden Riches

Hidden Riches Key of Light

Key of Light Divine Evil

Divine Evil High Noon

High Noon Blue Dahlia

Blue Dahlia Sea Swept

Sea Swept This Magic Moment

This Magic Moment Year One

Year One A Little Fate

A Little Fate Honest Illusions

Honest Illusions The Reef

The Reef Shelter in Place

Shelter in Place The Hollow

The Hollow Holding the Dream

Holding the Dream The Pagan Stone

The Pagan Stone Savour the Moment

Savour the Moment The Perfect Hope

The Perfect Hope Island of Glass

Island of Glass Happy Ever After

Happy Ever After Bed of Roses

Bed of Roses Stars of Fortune

Stars of Fortune Dark Witch

Dark Witch The Return of Rafe MacKade

The Return of Rafe MacKade Chesapeake Blue

Chesapeake Blue The Perfect Neighbor

The Perfect Neighbor The Collector

The Collector Come Sundown

Come Sundown Rebellion

Rebellion Affaire Royale

Affaire Royale Daring to Dream

Daring to Dream Bay of Sighs

Bay of Sighs Blood Magick

Blood Magick Angels Fall

Angels Fall Captivated

Captivated The Last Boyfriend

The Last Boyfriend Irish Thoroughbred

Irish Thoroughbred Inner Harbor

Inner Harbor The Right Path

The Right Path Night Shadow

Night Shadow The Heart of Devin MacKade

The Heart of Devin MacKade Shadow Spell

Shadow Spell The Playboy Prince

The Playboy Prince The Fall of Shane MacKade

The Fall of Shane MacKade Rising Tides

Rising Tides Command Performance

Command Performance Hidden Star

Hidden Star Cordina's Crown Jewel

Cordina's Crown Jewel The MacGregor Brides

The MacGregor Brides The Pride of Jared MacKade

The Pride of Jared MacKade Born in Ice

Born in Ice Whiskey Beach

Whiskey Beach The Last Honest Woman

The Last Honest Woman Night Shield

Night Shield Born in Shame

Born in Shame Secret Star

Secret Star Tempting Fate

Tempting Fate Nightshade

Nightshade The Obsession

The Obsession Night Shift

Night Shift Playing The Odds

Playing The Odds Tears of the Moon

Tears of the Moon One Man's Art

One Man's Art The MacGregor Groom

The MacGregor Groom Irish Rebel

Irish Rebel Morrigan's Cross

Morrigan's Cross In From The Cold

In From The Cold Night Smoke

Night Smoke Finding the Dream

Finding the Dream Red Lily

Red Lily The Liar

The Liar Montana Sky

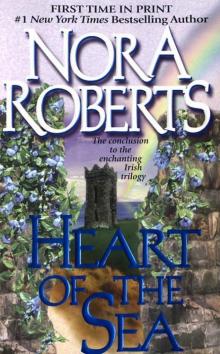

Montana Sky Heart of the Sea

Heart of the Sea All The Possibilities

All The Possibilities Opposites Attract

Opposites Attract Captive Star

Captive Star The Winning Hand

The Winning Hand Key of Valor

Key of Valor Courting Catherine

Courting Catherine Heaven and Earth

Heaven and Earth Face the Fire

Face the Fire Untamed

Untamed Skin Deep

Skin Deep Enchanted

Enchanted Song of the West

Song of the West Suzanna's Surrender

Suzanna's Surrender Entranced

Entranced Dance of the Gods

Dance of the Gods Key of Knowledge

Key of Knowledge Charmed

Charmed For Now, Forever

For Now, Forever Blood Brothers

Blood Brothers Sweet Revenge

Sweet Revenge Three Fates

Three Fates Mind Over Matter

Mind Over Matter Megan's Mate

Megan's Mate Valley of Silence

Valley of Silence Without A Trace

Without A Trace The Law is a Lady

The Law is a Lady Temptation

Temptation Dance to the Piper

Dance to the Piper Blue Smoke

Blue Smoke Black Hills

Black Hills The Heart's Victory

The Heart's Victory Sullivan's Woman

Sullivan's Woman Genuine Lies

Genuine Lies For the Love of Lilah

For the Love of Lilah Gabriel's Angel

Gabriel's Angel Irish Rose

Irish Rose Hot Ice

Hot Ice Dual Image

Dual Image Lawless

Lawless Catch My Heart

Catch My Heart Birthright

Birthright First Impressions

First Impressions Chasing Fire

Chasing Fire Carnal Innocence

Carnal Innocence Best Laid Plans

Best Laid Plans The Villa

The Villa Northern Lights

Northern Lights Local Hero

Local Hero Island of Flowers

Island of Flowers The Welcoming

The Welcoming All I Want for Christmas

All I Want for Christmas Black Rose

Black Rose Hot Rocks

Hot Rocks Midnight Bayou

Midnight Bayou The Art of Deception

The Art of Deception From This Day

From This Day Less of a Stranger

Less of a Stranger Partners

Partners Storm Warning

Storm Warning Once More With Feeling

Once More With Feeling Her Mother's Keeper

Her Mother's Keeper Sacred Sins

Sacred Sins Rules of the Game

Rules of the Game Sanctuary

Sanctuary Unfinished Business

Unfinished Business Cordina's Royal Family Collection

Cordina's Royal Family Collection Dangerous Embrace

Dangerous Embrace One Summer

One Summer The Best Mistake

The Best Mistake Boundary Lines

Boundary Lines Under Currents

Under Currents The Stanislaski Series Collection, Volume 1

The Stanislaski Series Collection, Volume 1 The Rise of Magicks

The Rise of Magicks The Rise of Magicks (Chronicles of The One)

The Rise of Magicks (Chronicles of The One) The Awakening: The Dragon Heart Legacy Book 1

The Awakening: The Dragon Heart Legacy Book 1 Dance of Dreams

Dance of Dreams Skin Deep: The O'Hurleys

Skin Deep: The O'Hurleys The Quinn Legacy: Inner Harbor ; Chesapeake Blue

The Quinn Legacy: Inner Harbor ; Chesapeake Blue![[Chronicles of the One 03.0] The Rise of Magicks Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/11/chronicles_of_the_one_03_0_the_rise_of_magicks_preview.jpg) [Chronicles of the One 03.0] The Rise of Magicks

[Chronicles of the One 03.0] The Rise of Magicks Times Change

Times Change Dance to the Piper: The O'Hurleys

Dance to the Piper: The O'Hurleys Christmas In the Snow: Taming Natasha / Considering Kate

Christmas In the Snow: Taming Natasha / Considering Kate Waiting for Nick

Waiting for Nick Summer Desserts

Summer Desserts Dream 2 - Holding the Dream

Dream 2 - Holding the Dream The Novels of Nora Roberts, Volume 2

The Novels of Nora Roberts, Volume 2 In the Garden Trilogy

In the Garden Trilogy Eight Classic Nora Roberts Romantic Suspense Novels

Eight Classic Nora Roberts Romantic Suspense Novels Best Laid Plans jh-2

Best Laid Plans jh-2 From the Heart

From the Heart Holiday Wishes

Holiday Wishes Dream 1 - Daring to Dream

Dream 1 - Daring to Dream Second Nature

Second Nature Summer Pleasures

Summer Pleasures Once Upon a Castle

Once Upon a Castle Stars of Mithra Box Set: Captive StarHidden StarSecret Star

Stars of Mithra Box Set: Captive StarHidden StarSecret Star Impulse

Impulse The Irish Trilogy by Nora Roberts

The Irish Trilogy by Nora Roberts The Pride Of Jared Mackade tmb-2

The Pride Of Jared Mackade tmb-2 Lawless jh-3

Lawless jh-3 Taming Natasha

Taming Natasha Endless Summer

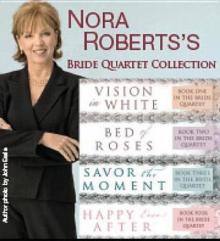

Endless Summer Bride Quartet Collection

Bride Quartet Collection Happy Ever After tbq-4

Happy Ever After tbq-4 Heart Of The Sea goa-3

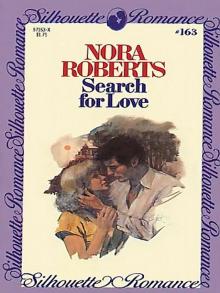

Heart Of The Sea goa-3 Search for Love

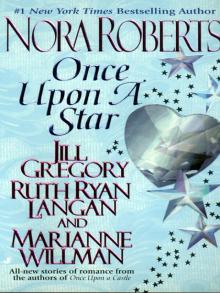

Search for Love Once upon a Dream

Once upon a Dream Once Upon a Star

Once Upon a Star Dream Trilogy

Dream Trilogy Risky Business

Risky Business The Novels of Nora Roberts, Volume 3

The Novels of Nora Roberts, Volume 3 Dream 3 - Finding the Dream

Dream 3 - Finding the Dream Promises in Death id-34

Promises in Death id-34 The Novels of Nora Roberts, Volume 4

The Novels of Nora Roberts, Volume 4 The Perfect Hope ib-3

The Perfect Hope ib-3 Less than a Stranger

Less than a Stranger Savour the Moment: Now the Big Day Has Finally Arrived, It's Time To...

Savour the Moment: Now the Big Day Has Finally Arrived, It's Time To... Convincing Alex

Convincing Alex Bed of Roses tbq-2

Bed of Roses tbq-2 Savour the Moment tbq-3

Savour the Moment tbq-3 Lessons Learned

Lessons Learned Key Of Valor k-3

Key Of Valor k-3 Red lily gt-3

Red lily gt-3 Savor the Moment

Savor the Moment The Return Of Rafe Mackade tmb-1

The Return Of Rafe Mackade tmb-1 For The Love Of Lilah tcw-3

For The Love Of Lilah tcw-3 Black Rose gt-2

Black Rose gt-2 Novels: The Law is a Lady

Novels: The Law is a Lady Chesapeake Bay Saga 1-4

Chesapeake Bay Saga 1-4 Considering Kate

Considering Kate Moon Shadows

Moon Shadows Key of Knowledge k-2

Key of Knowledge k-2 The Sign of Seven Trilogy

The Sign of Seven Trilogy Once Upon a Kiss

Once Upon a Kiss The Novels of Nora Roberts, Volume 5

The Novels of Nora Roberts, Volume 5 Suzanna's Surrender tcw-4

Suzanna's Surrender tcw-4 The Quinn Brothers

The Quinn Brothers Falling for Rachel

Falling for Rachel Brazen Virtue

Brazen Virtue Time Was

Time Was The Gallaghers of Ardmore Trilogy

The Gallaghers of Ardmore Trilogy Megan's Mate tcw-5

Megan's Mate tcw-5 Loving Jack jh-1

Loving Jack jh-1 Rebellion & In From The Cold

Rebellion & In From The Cold Blue Dahlia gt-1

Blue Dahlia gt-1 The MacGregor Grooms

The MacGregor Grooms The Next Always tibt-1

The Next Always tibt-1 The Heart Of Devin Mackade tmb-3

The Heart Of Devin Mackade tmb-3 The Novels of Nora Roberts Volume 1

The Novels of Nora Roberts Volume 1 Treasures Lost, Treasures Found

Treasures Lost, Treasures Found Nora Roberts's Circle Trilogy

Nora Roberts's Circle Trilogy The Key Trilogy

The Key Trilogy The Fall Of Shane Mackade tmb-4

The Fall Of Shane Mackade tmb-4 A Will And A Way

A Will And A Way Jewels of the Sun goa-1

Jewels of the Sun goa-1 Luring a Lady

Luring a Lady